Around the world, fishermen are using explosives, often with dynamite, to maximize their catch. Called blast fishing or dynamite fishing, the practice goes on in nations from Lebanon and Malaysia to the Philippines, while some countries—Kenya and Mozambique, for instance—have managed to stamp it out.

In Africa, Tanzania is the only country where blast fishing still occurs on a large scale—and it’s happening at unprecedented rates. “I would say probably for the last five years it’s at least as bad or worse than it’s ever been,” said Jason Rubens, a marine conservationist with World Wildlife Fund’s Tanzania branch.

In December, Wildlife Watch wrote about blast fishing after researchers from the Wildlife Conservation Society released a report documenting the extent of the illegal practice in the Indian Ocean off Tanzania. The researchers counted more than 300 explosions in 30 days, from the Kenya-Tanzania border down to Mozambique. That’s at least 10 blasts a day.

Reference and Citation: National Geographic

(https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/06/blast-fishing-dynamite-fishing-tanzania/)

Dynamite fishing, otherwise known “blast fishing,” is illegal in many parts of the world, but despite government crackdowns, the practice is difficult for authorities to contain. Dynamite fishing is common across Southeast Asia’s Coral Triangle, and Tanzania has seen a resurgence of the practice as mining activity in the country has made dynamite more readily available.

Blast fishing isn’t a new technique. It was introduced to many countries by European armies. During World War I, it was common for soldiers to use grenades catch a quick meal.

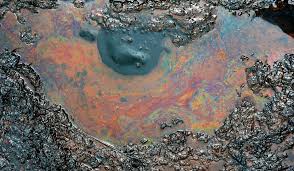

Dynamite fishing shatters fragile coral colonies. Even the smallest piece of dynamite can blast a crater two to three feet in diameter. The blast kills coral tissues, and the surrounding rubble prevents adjacent coral colonies from recovery. If the shallow part of the reef is decimated by repeated blasts, it’s impossible for the reef to recover. Many bomb fishermen don’t understand that once the reefs are gone, the fish will go too. It’s estimated that over 55 percent of the world’s reefs are threatened by overfishing and/or destructive fishing.

Reference and Citation: Aquaviews

(https://www.leisurepro.com/blog/ocean-news/effects-dynamite-fishing-coral-reefs/)

Impact on Animal Life

TRCC indicates that animals other than fish, including sea turtles, can be affected by the explosions from blast fishing. To make matters worse, the AWI says that the explosives used in blast fishing are often made with fertilizers and kerosene, which can act as environmental pollutants when they are introduced into marine environments. Endangered species will be affected in more ways than one by blast fishing, and more and more species will become endangered as a result.

Long Term Business Effects

Sievert indicates that in the long run, blast fishing damages fish yields by damaging the marine ecosystems that sustain those yields in the first place. Fishers that rely on blast fishing may be making a profit in the short-term, but they are ultimately disrupting their long-term business interests. However, Sievert alludes to the difficulty of convincing certain blast fishers that their fishing methods are ultimately untenable, which is one of the challenges involved with ending blast fishing for good.

Blast Fishing in the Future

The negative consequences of blast fishing are increasingly well-documented, which may or may not make a difference. The legal, economic, and political circumstances involving blast fishing will not last forever, but it is possible that blast fishing and the associated problems will persist for years to come.

Reference and Citation: Love to Know

(https://greenliving.lovetoknow.com/environmental-issues/what-is-blast-fishing)

According to the initial findings of a survey of Philippine coral reefs conducted from 2015 to 2017 and published in the Philippine Journal of Science, there are no longer any reefs in excellent condition, and 90 percent were classified as either poor or fair. A 2017 report by the United Nations predicts that all 29 World Heritage coral reefs, including one in the Philippines, will die by 2100 unless carbon emissions are drastically reduced. “It is a bit dismal,” said Porfirio Alino, a research professor specializing in corals at the Marine Science Institute at the University of the Philippines in Diliman.

The effects of climate change — warming waters and acidification that cause coral bleaching and push some reefs to death — are difficult to address. But if the stresses caused by human activity can be stopped, Dr. Alino explained, coral reefs have a better chance of surviving.

In 2014, the European Union issued a yellow card to the Philippines warning that it would be banned from exporting to the bloc unless its fishing activities were better regulated. In response, the Philippines produced a new fisheries code that called for stricter measures against illegal methods and commercial overfishing. In 2015, the yellow card was lifted.

“Our law is harsh, painful and swift,” said Eduardo Gongona, director of the Philippine Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. “We have no pity on illegal fishers and illegal fishing.” Gloria Ramos, vice president of Oceana Philippines, a nongovernmental organization for ocean conservation, agreed that the new laws were strong but said they were not being properly implemented because of the influence the commercial fishing industry has over government officials. Despite signs that Philippine fisheries are collapsing, Ms. Ramos said, “there is no sense of urgency.”

Reference and Citation: The New York Times

(https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/15/world/asia/philippines-dynamite-fishing-coral.html)